Palden is from Amdo Tibet, Qinghai, China. His work with the PASTRES project explores hybrid process of land control in pastoral areas of Qinghai, in the context of rising uncertainties on the Tibetan plateau.

above

Members of the monastic wildlife conservation association carry fodder for the blue sheep during wintertime in Golok.

Members of the monastic wildlife conservation association carry fodder for the blue sheep during wintertime in Golok.

below

More and more pastoralists from the Kokonor region choose to stay on their winter pasture during summertime to earn extra income from tourist activities such as yak and horse riding.

More and more pastoralists from the Kokonor region choose to stay on their winter pasture during summertime to earn extra income from tourist activities such as yak and horse riding.

golOk

average altitude:

4200 m

4200 m

livestock composition:

Yak

Yak

distance to township center:

76 km

76 km

suitability for tourism:

Less suitable

Less suitable

natural resources:

Rich in caterpillar fungus

Rich in caterpillar fungus

state investment:

County government funded small-scale tourism centre

County government funded small-scale tourism centre

ethnic composition:

Tibetan

Tibetan

kokoNor

average altitude:

3196 m

3196 m

livestock composition:

Sheep and yak

Sheep and yak

distance to township center:

4 km

4 km

suitability for tourism:

Very suitable

Very suitable

natural resources:

None

None

state investment:

Provincial government funded major tourism hotspots, the coming Lake National Park

Provincial government funded major tourism hotspots, the coming Lake National Park

ethnic composition:

Tibetan, Chinese, Hui Muslim, Mongolian

Tibetan, Chinese, Hui Muslim, Mongolian

the disAppearing guRu

1.

Local pastoralists worship guru Rinpoche, as the mighty Buddhist teacher from India, and as a saviour of the land and the people. To commemorate the guru, local pastoralists constructed a bronze statue by the lake, with prayer wheels surrounded for devotees to accumulate merits. And the statue has attracted many pilgrims who come pilgrimage the lake every year.2.

Pastoralists invested a total of 150,000 yuan into the statue and its surroundings, expecting to recover some of the money by charging entrance fees to non-locals and non-Tibetan tourists. However, the lake expansion has dramatically affected these earnings. As one nearby resident stated,‘You can see the statue from your car, and they used to come and walk around the statue and take selfies with the Rinpoche. But now, they don’t, because the guru is in the water and you cannot take a close look.

Apa J, Jan, Kokonor, 2020

3.

Pastoralists eventually had to remove their mighty guru Rinpoche due to the lake expansion. As Awo, a pastoralist in his late 50s, stated,‘the lake is expanding, pastoralists are losing their land, and the government is using this chance to boast about their conservational effort in this area, which is driving the province to promoting the idea of designing this area into a national park.’

A growing number of resettlement communities are seen in many of the pastoralist townships in Amdo Tibet. Many have thrived from state-led development and progress-oriented projects such as ‘ecological civilization building’ and the ‘poverty alleviation and eradication campaign’.

The yaK

and bEauty conTest

The yaK

and bEauty conTest

top:

Judges tally the votes.

Judges tally the votes.

midle

One of the hosts of the beauty contest and her child.

One of the hosts of the beauty contest and her child.

bottom

Attendees photograph the winning yak.

Attendees photograph the winning yak.

Since there are no more sheep in Lun Mo Chee village, local pastoralists treat the yak as the most treasured animal. Yaks are widely used for many occasions and activities. For instance, during the annually organized ‘Dre Mo Beauty Contest,’ female yaks compete for the championship and a cash prize.

‘You know, we lost our sheep, and I am afraid that they (sheep) will never come back. Now we just have the yak and the horse, and comparatively, yaks are more important than horses here. However, pastoralists, especially young pastoralists, are abandoning yaks too. They sell their yak at a low price, and some of them even give up on pastoralism and move to urban areas. There are so many uncertainties out there, especially with the decreased price of the caterpillar fungus these years. As pastoralists, life has to depend on animals - that is the essence of being a pastoralist - and that is why we need to re-establish the significance and the value of the yaks, and this is why we organize such a contest. We want to motivate people, to promote the sense of raising yaks in the community, and to try to encourage pastoralists to invest more time and effort in their animals.’

“Young pastoralists are abandoning yaks too.”

The monaStery and the pasToralist

In Golok, the township primary school is 74 km away from the winter pasture, a 3-5 hour drive due to poor road conditions. Many pastoralists prefer to send kids to the monastic primary school, which is close to their winter homes. Moreover, pastoralists consider the monastic primary school a much better place for the kids to learn Tibetan reading and writing.

The practice of Tibetan Buddhist rituals is one of the strategies that local pastoralists use to respond to uncertainties. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kokonor pastoralists made thousands of statues and buried them underground for better luck in the coming year.

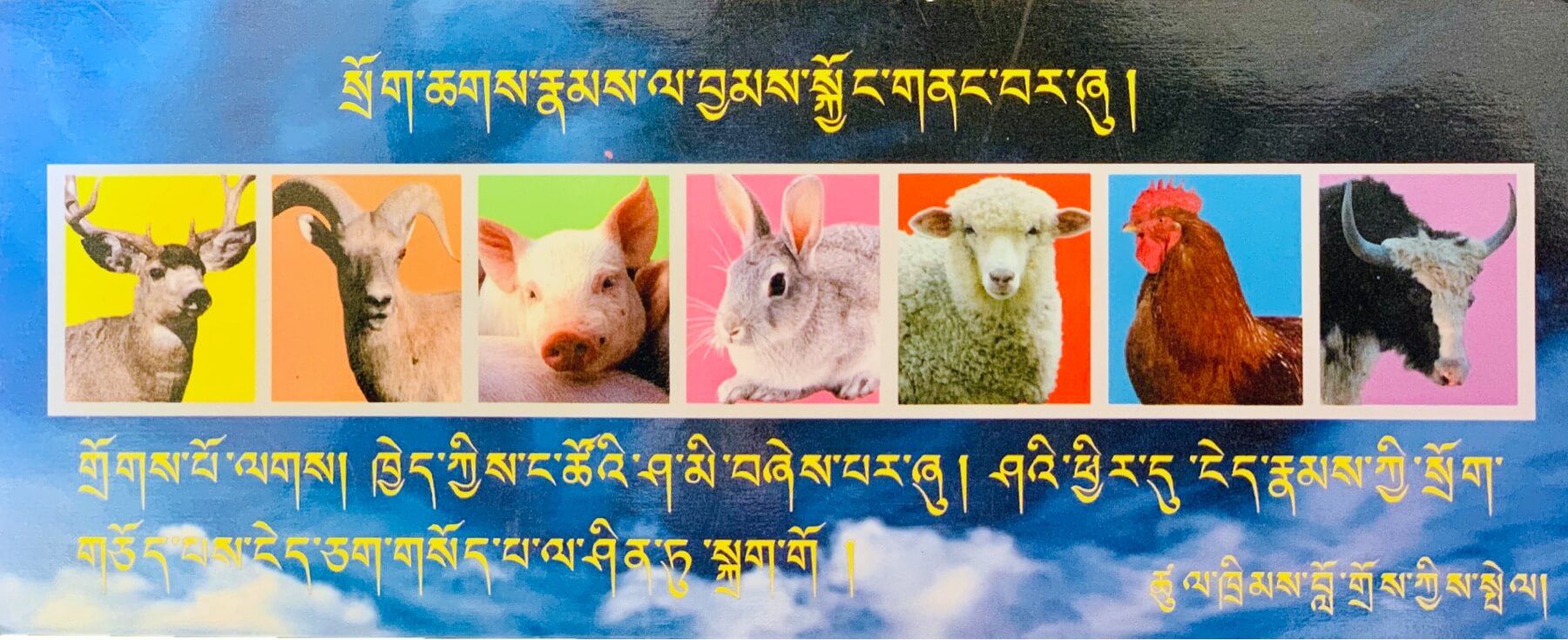

“Dear [human] friends,

please don’t kill us and eat our meat.”

- Tsul Lo (a well-known Buddhist teacher from Kham Tibet)

Uncle Ray bought these two sheep from the butcher during the winter of 2019 for 1000 yuan. The family will herd the sheep until they die, whether by snowstorm, wildlife attack or natural death.

Setting livestock free is an existing religious practice for merit accumulation in Tibet. ‘Animal releasing’ originated from the idea of ‘no-harming’ from Buddhist teaching. After he shopped for the Tibetan New Year, Uncle Ray, who is a Buddhist, decided to purchase the sheep for the merit of the whole family for the coming year.

Setting livestock free is an existing religious practice for merit accumulation in Tibet. ‘Animal releasing’ originated from the idea of ‘no-harming’ from Buddhist teaching. After he shopped for the Tibetan New Year, Uncle Ray, who is a Buddhist, decided to purchase the sheep for the merit of the whole family for the coming year.

Two pastoralists organized this animal releasing on a county street in Golok. From the gathered audience, a total of 5000 yuan was donated within an hour. The two buyers of the two yaks were satisfied, since they paid a total of 5300 yuan to the butcher, and they would pay the remaining 300 yuan for good conduct.

The ultimate goal of life-releasing is to secure the livestock from being butchered, slaughtered and eaten.

The ultimate goal of life-releasing is to secure the livestock from being butchered, slaughtered and eaten.

credits:

All photography by Palden Tsering.

Photovoice Advisor: Shibaji Bose

Photo Editing and Newspaper Design: Roopa Gogineni