By Roopa Gogineni

︎︎︎download newspaper

‘Uncertainty’ in Italian is literally translated as incertezza. Other terms that are used in the Sardinian context are precarieta (precarity), insicurezza (insecurity) and imprevisto (unexpected event).

For pastoralists, precarity and uncertainty are the only constants. When making plans, they rarely say yes, instead they say: ‘Barring unforeseen events, I will be there.’ As a pastoralist from the South shared,

‘Uncertainty is there everyday... uncertainty around whether to continue or not because it is becoming less and less profitable and difficult to predict from an economic point of view.’

Pastoralists will say that it is not convenient, not possible to continue doing what they do, it is not worth it, the future is uncertain, and their sons and daughters do not want to continue this job. In many cases, it is the pastoralists themselves who wish a better, less precarious future for their children. Nevertheless, pastoralists keep doing what they do because, with centuries of experience, they have acquired a sensibility, an instinct and a capacity to deal with uncertainty that words often fail to explain. This almost assumes a mystical connotation, they cannot control unforeseen circumstances, they resign themselves to this uncertain reality, they accept it with tolerance and patience.

What comes toyour mind when I say the word ‘uncertain’ (al majhoul or aashakk)?

‘When there is no rain it’s hard. It’s quite difficult. Thankfully, I manage the livestock on my own. If I ask a herder to be responsible for the herd, along with the increase in forage and barley prices... I wouldn’t make it... I do not have the resources to resist. I contribute with my own money, my family is helping me a bit, we rise and fall, and we thank God. This is uncertainty. One day the livestock eat, the next day they don’t. And hopefully, since we have in our pocket some money, we will provide the flock what’s necessary for their needs. Living is hard, especially when there is no rain, hard. Along with the high cost of living, in our time it got harder.’

Multiple terms of uncertainty are in use in Borana, including hinbanne (not known or unknown), haala or jilbii hinbanne (limited knowledge, not knowing the likelihood) and mamii (unexpected).

Qaballe Malich (female, age 38) observes,

Focusing on droughts, Jarso Godana (male, age 61) explains, ‘If we talk about the uncertainty of rain, there are various issues around it. It’s distribution, amount, and seasonality. We must ask if the failure of rain is accompanied by strong sunlight, wind or humidity? If it is windy, there might be somba [livestock respiratory disease]. If there is too much heat, dehydration might destroy livestock.’

Qaballe Malich (female, age 38) observes,

‘Uncertainty is your limited knowledge of when and how vital resources for your livelihood will diminish… in most cases, the availability of those resources is meaningless unless you have command over them.’

Focusing on droughts, Jarso Godana (male, age 61) explains, ‘If we talk about the uncertainty of rain, there are various issues around it. It’s distribution, amount, and seasonality. We must ask if the failure of rain is accompanied by strong sunlight, wind or humidity? If it is windy, there might be somba [livestock respiratory disease]. If there is too much heat, dehydration might destroy livestock.’

‘Everything is Mi Rtag Ba [what happened is already the past], and what is going to happen is unpredictable; all we can depend on is the present, what happens now, we deal with it now.’

Nges Ba Med Ba means that something is unsure. Nges Med is not focusing on the consequences, it only focuses on the unknown state of things.

Bsam Yul Las Das Ba is something beyond one’s imagination, beyond the realm of thought. If something is Bsam Yul Las Das Ba, then it is unmeasurable, unpredictable, unexpected, and impossible to prepare for.

When asked if they could predict certain events, like the pandemic or the first rainfall, or whether they knew to expect such events, the Rabari pastoralists shrug their shoulders and say kone khabar, ‘who knows? We don’t know’ and ‘only God knows.’ They tend not to speculate on events, especially those that they cannot control, and live in the here and now.

Instead of speculating they say thaay tyaare hachu or

Instead of making assumptions, they wait for phenomena to manifest in reality and respond to continuously changing circumstances.

Being religious people, they accept what comes as the will of God, as destiny or bhagya. They do not question or lament happenings.

Instead of speculating they say thaay tyaare hachu or

‘it will be true when it happens/ it will be known when it happens.’

Instead of making assumptions, they wait for phenomena to manifest in reality and respond to continuously changing circumstances.

Being religious people, they accept what comes as the will of God, as destiny or bhagya. They do not question or lament happenings.

According to pastoralists in Isiolo, northern Kenya, uncertainty is hinbeennee (lack of knowledge), seeti (doubt) or hiin huubbaannee (being unsure about a given condition, context or the future).

No human knows everything, even if you are expert in one area, explains one elder. Hooraa buulaan (whoever desires prosperous life) will survive all the c’inna (calamities) that we face the society. Abdullahi Dima observes that individuals who desire a successful life are always in fear of the unknown (hooraa Buulaan waa soodaataa) and must know how to handle those fears without harming others. We have to be cautious of the surroundings and avoid causing harm or danger (hooraan Bulaan mirgaa biitaa ufl aalaa).

‘Naamii eegii d’aalaatee gaam tookkoon d’aalle’ (humans are always ignorant on one side).

No human knows everything, even if you are expert in one area, explains one elder. Hooraa buulaan (whoever desires prosperous life) will survive all the c’inna (calamities) that we face the society. Abdullahi Dima observes that individuals who desire a successful life are always in fear of the unknown (hooraa Buulaan waa soodaataa) and must know how to handle those fears without harming others. We have to be cautious of the surroundings and avoid causing harm or danger (hooraan Bulaan mirgaa biitaa ufl aalaa).

shocks and stresses

The interdependence between pastoral life and the natural world is acutely felt during floods, storms, snowfall, drought, wildlife attacks, locusts, pandemics, an expanding lake. Amidst our changing climate, these disturbances often overlap or are new in size and speed, testing the practised adaptive strategies of pastoral communities.

top: ‘Bofa dheedhiitti, buutii afaan buune.’ When we attempted to flee from a bofa snake (less deadly), we were met with butti (most poisonous snake).

It is believed that rain follows locusts. Both events occurred in 2020: modest rains at the start of the long rain season (March), which increased following the arrival of a tiny swarm of locusts. However, this provided an ideal environment for locusts to multiply, and they wreaked havoc on newly planted crops and fresh grassland. Pastoralists reoriented their strategy to deal with the situation, but mobility - a key feature of the pastoral coping strategy - was halted to contain the spread of COVID-19. This combination of shocks has devastated many pastoralists in Borana.

left: ‘When livestock disappear, they are not easy to recover; the entire area is covered by the thorny ‘mathenge’ (Prosopis Juliflora) and other shrubs. We took the flock to a place called Goo’aa near the ‘galaan’ (river) to feed on a ‘d’igajii’ shrub, which is not as thorny. The goats dispersed and a lion attacked and killed 84 goats. We kept searching with the help of other herders but only found the carcasses; the lion killed them all without eating any flesh! It was very disheartening. I reported this to the chief, received a letter and followed it up with the County government. It has been five years since then, and I have never been compensated.’ - Ali Saleisa, Merti Resident, February 2020.

It is believed that rain follows locusts. Both events occurred in 2020: modest rains at the start of the long rain season (March), which increased following the arrival of a tiny swarm of locusts. However, this provided an ideal environment for locusts to multiply, and they wreaked havoc on newly planted crops and fresh grassland. Pastoralists reoriented their strategy to deal with the situation, but mobility - a key feature of the pastoral coping strategy - was halted to contain the spread of COVID-19. This combination of shocks has devastated many pastoralists in Borana.

left: ‘When livestock disappear, they are not easy to recover; the entire area is covered by the thorny ‘mathenge’ (Prosopis Juliflora) and other shrubs. We took the flock to a place called Goo’aa near the ‘galaan’ (river) to feed on a ‘d’igajii’ shrub, which is not as thorny. The goats dispersed and a lion attacked and killed 84 goats. We kept searching with the help of other herders but only found the carcasses; the lion killed them all without eating any flesh! It was very disheartening. I reported this to the chief, received a letter and followed it up with the County government. It has been five years since then, and I have never been compensated.’ - Ali Saleisa, Merti Resident, February 2020.

Top: In the past in southern Ethiopia, the stress was the risk of rain failure, but in recent years, floods have destroyed crops and killed animals.

Middle: A pastoralist in Kokonor, Amdo Tibet, gazes at his former pasture, now lost under an expanding lake.

Bottom: School closures during the COVID pandemic, a boon for the daily labour supply in Ethiopia.

Middle: A pastoralist in Kokonor, Amdo Tibet, gazes at his former pasture, now lost under an expanding lake.

Bottom: School closures during the COVID pandemic, a boon for the daily labour supply in Ethiopia.

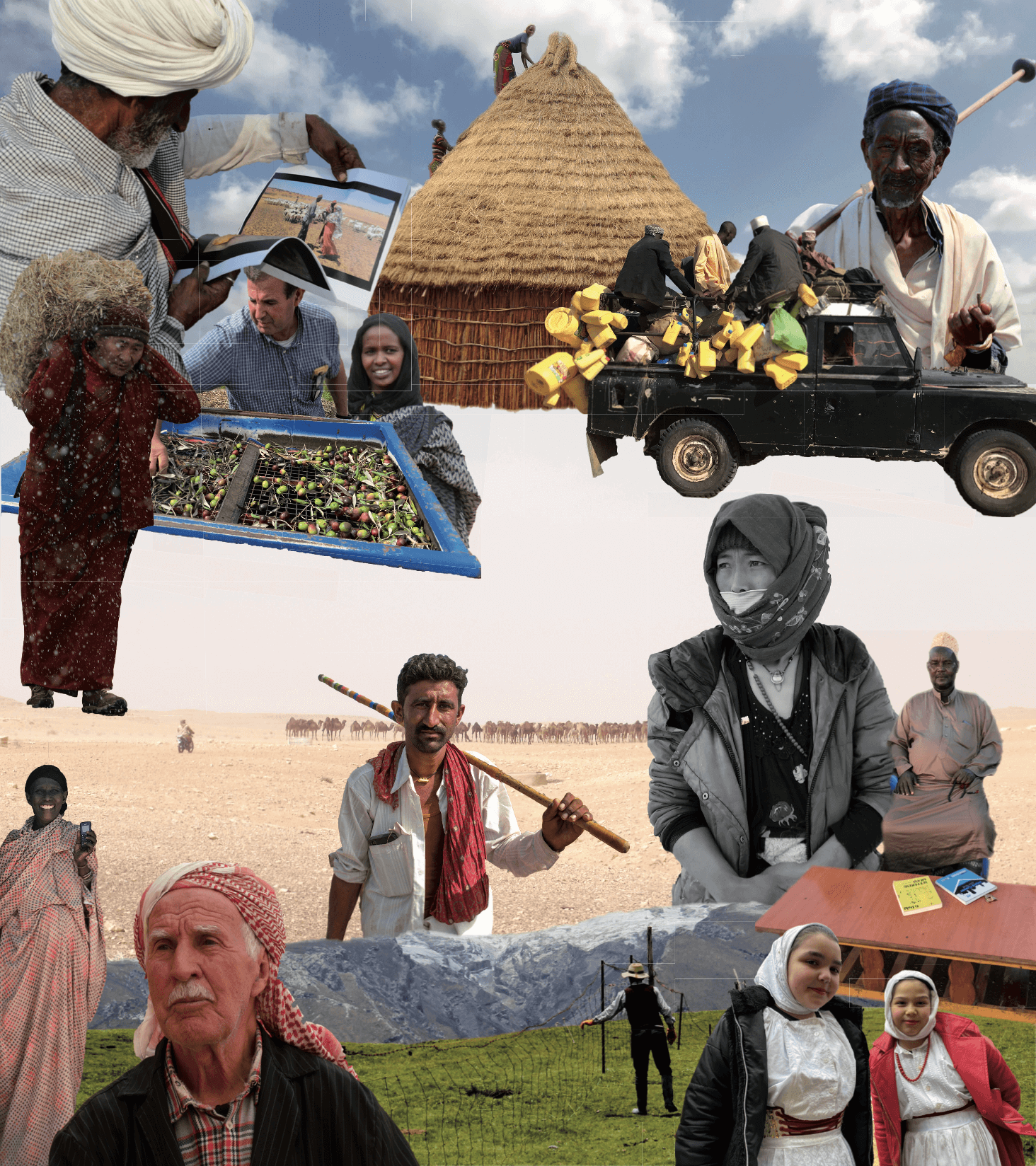

diversification

Facing diverse uncertainties, pastoral communities constantly reconfigure livelihoods. Livestock keepers are occasional farmers, tour guides, foragers, bakers, miners, olive pickers, shopkeepers.

top-left

A woman makes and sells liquor out of her home. She indicates whether she is open for business with a yellow cup.

A woman makes and sells liquor out of her home. She indicates whether she is open for business with a yellow cup.

top-middle&right

Many pastoralists blame the rocketing price of the caterpillar fungus (a medicinal product) for the decline in livestock in Lun Mo Chee, especially for the disappearance of sheep. Caterpillar fungus harvesting is now one of the most important non-herding pastoral activities each year. The harvest lasts a total of 45 days from early May to mid-June and the price of the caterpillar fungus determines family incomes, investments in livestock (animal, forage, land leasing and so on), bank loans and other expenditures.

Many pastoralists blame the rocketing price of the caterpillar fungus (a medicinal product) for the decline in livestock in Lun Mo Chee, especially for the disappearance of sheep. Caterpillar fungus harvesting is now one of the most important non-herding pastoral activities each year. The harvest lasts a total of 45 days from early May to mid-June and the price of the caterpillar fungus determines family incomes, investments in livestock (animal, forage, land leasing and so on), bank loans and other expenditures.

bottom-left

Pastoralists harvesting teff, a crop they do not consume themselves. ‘We sniff opportunities, and we grab them. We are pragmatic. We are not pastoralists by choice; rather, we know it is vital in such environmental conditions. That does not mean we should stick with it [pastoralism] when things change, we should look for ways of supporting it.’ -Doyo, male, 62, Feb 28, 2020.

Pastoralists harvesting teff, a crop they do not consume themselves. ‘We sniff opportunities, and we grab them. We are pragmatic. We are not pastoralists by choice; rather, we know it is vital in such environmental conditions. That does not mean we should stick with it [pastoralism] when things change, we should look for ways of supporting it.’ -Doyo, male, 62, Feb 28, 2020.

bottom-middle

The olives are ready to be pressed. Pastoralists diversify according to the territory in which they live, producing oil, wine, or other forest products such as chestnuts, wood etc.

The olives are ready to be pressed. Pastoralists diversify according to the territory in which they live, producing oil, wine, or other forest products such as chestnuts, wood etc.

bottom-right

A pastoralist hanging pork sausages made in winter. The majority of pastoralists have pigs and make products for family consumption and some for small sale, gifts, or other exchanges.

A pastoralist hanging pork sausages made in winter. The majority of pastoralists have pigs and make products for family consumption and some for small sale, gifts, or other exchanges.

social networks,

moral economies

The connective tissue of pastoral systems exists online, around a fire, at a sheep-shearing. In Sardinia, milk is pooled and cheese is made together. In Golok, Ambo Tibet, a crowd gathers for an annual yak beauty contest. These nurtured relations generate and renew forms of resilience, individual and collective alike.

Harki tokkin naaf naama hindiqu (one hand cannot wash the body). Livestock management is a task that is very difficult to be managed individually. It is a livelihood where solidarity, labour exchange and protection are fundamental. Exchanging labour includes watering the animals, herding the livestock and assisting in livestock management such as branding the animal. All these exchanges form part of the pastoral moral economy, and everyone should contribute for livelihoods to prosper.

Conversations about potential grazing spots, the next day’s route, the weather, events, ceremonies and rituals, and social relations abound as the members of a Rabari migrating group in Kaachchh gather around a fire after a hard day’s work.

The jezz, or sheep shearing season, marks the beginning and the end of the pastoral year in the southern regions of Tunisia. Extended family members of the various arch (tribes) meet in celebration, to help with the shearing of the community members’ stock. This reciprocal, non-monetary form of aid is called twiza in Amazigh. It is an informal system that cuts across family ties and social status. Twiza is practised in ceremonies (marriage and funerals), construction (upkeep of the troglodytic homes), agriculture (building of various barriers to manage water, olive picking) and livestock-rearing (shearing). Today however, emigration and the scattering of networks is slowly resulting in the substitution of reciprocal aid for waged labour. Sheep shearing, for example, no longer maintains the same quality of celebration and twiza that it once did.

mobility

Daily or seasonal movement enables exploiting diverse environments, relationships and economies. A configuration of old and new transportation infrastructure allows for pastoralists to be mobile amidst uncertainty.

Donkeys continue to be the invisible vessels for sheep and goat herders. Towards the end of an interview, I was once reprimanded by a pastoralist for forgetting to ask the most fundamental question ‘you forgot to ask about our donkeys and dogs, without them we would not be able to do our work’. Donkeys allow herders to travel further and remain independent from external support in the rocky terrain of southern Tunisia.

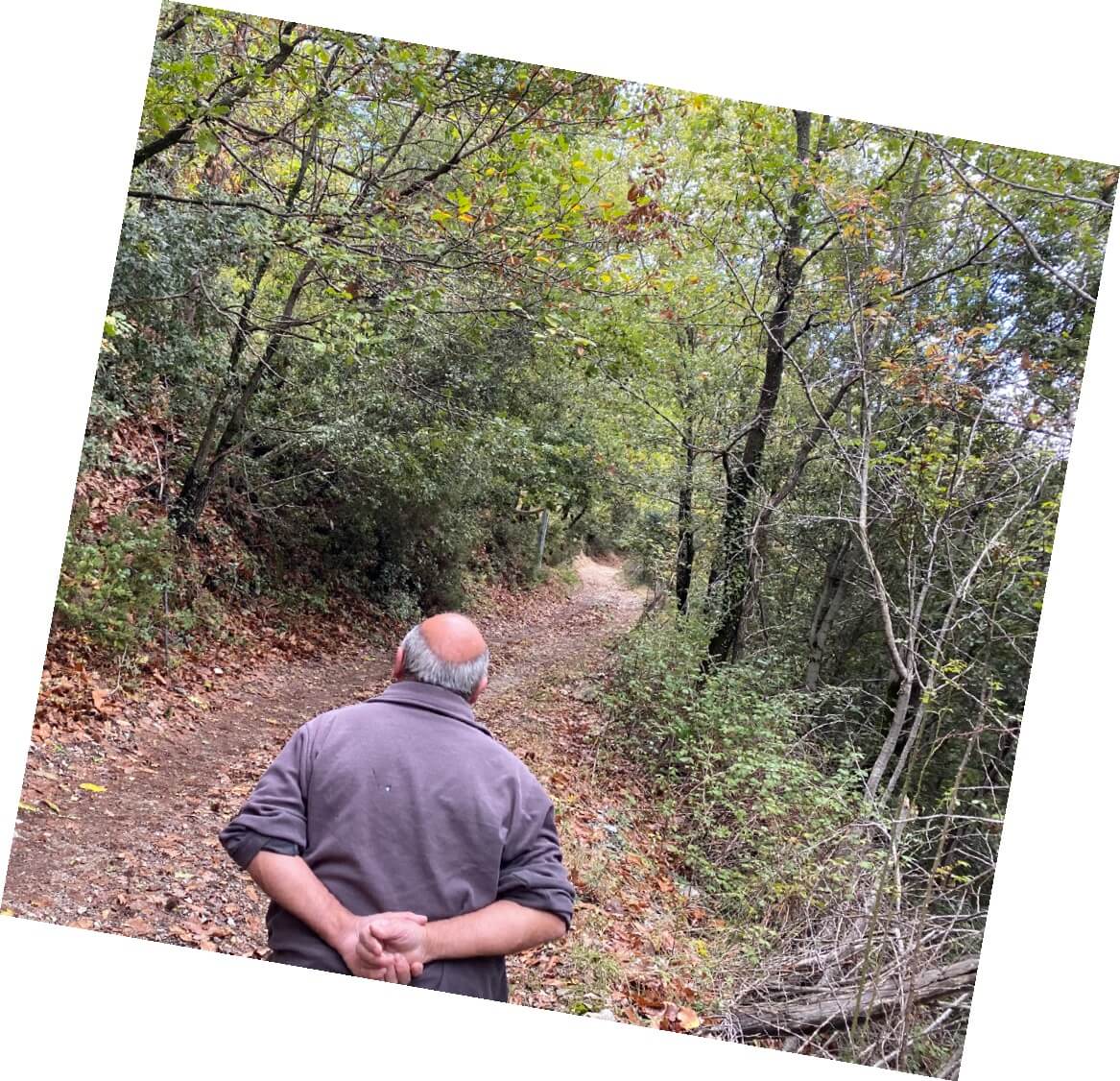

top to bottom: A pastoralist on horseback in Golok, Amdo Tibet; In Sardinia, a pastoralist walks to his mountain pasture; Rabari pastoralists push a truck out of the mud in Kachchh; A truck moves a yak in Amdo Tibet

Kachchh is an island separated from mainland Gujarat by sea incursions. The Rabari pastoralists graze their flocks on crop residues in agricultural hotspots on the mainland during summer and winter before moving back to the commons in Kachchh for the monsoon months. The only way to cross over is via the bridge at Surajbari. The shepherds walk the adult animals through the old Surajbari bridge, while the young lambs and the migrating camp travel via tractor over the new bridge rather than on foot and camel like on other days.

negotiating

authority

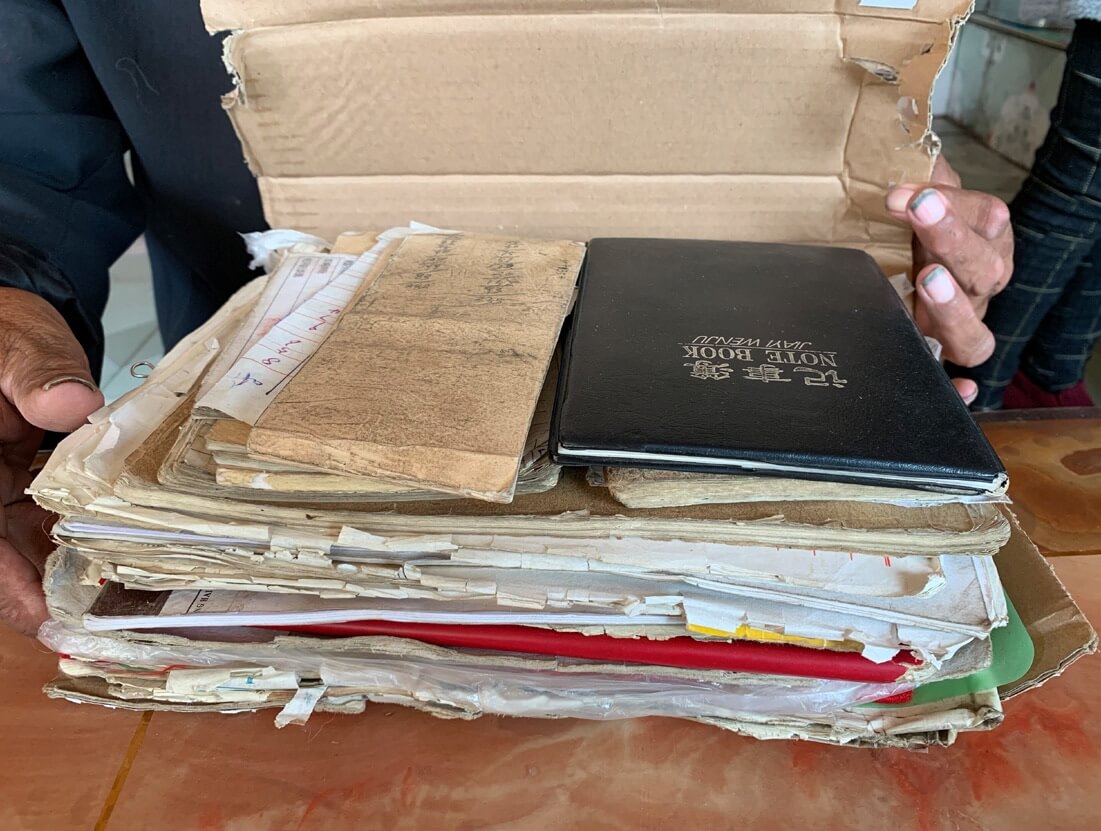

Responding to uncertainty means negotiating authority. From everyday protests of making cheese without accreditation, to direct engagements with the state, the points of contact between institutions and pastoral lives are many and constantly brokered. Authority is materialised through calendars, photographs, reports, notebooks. In the landscape the imposition of state authority can be observed in a resettlement village, while the resistance may be mobilised beneath an Acacia tree.

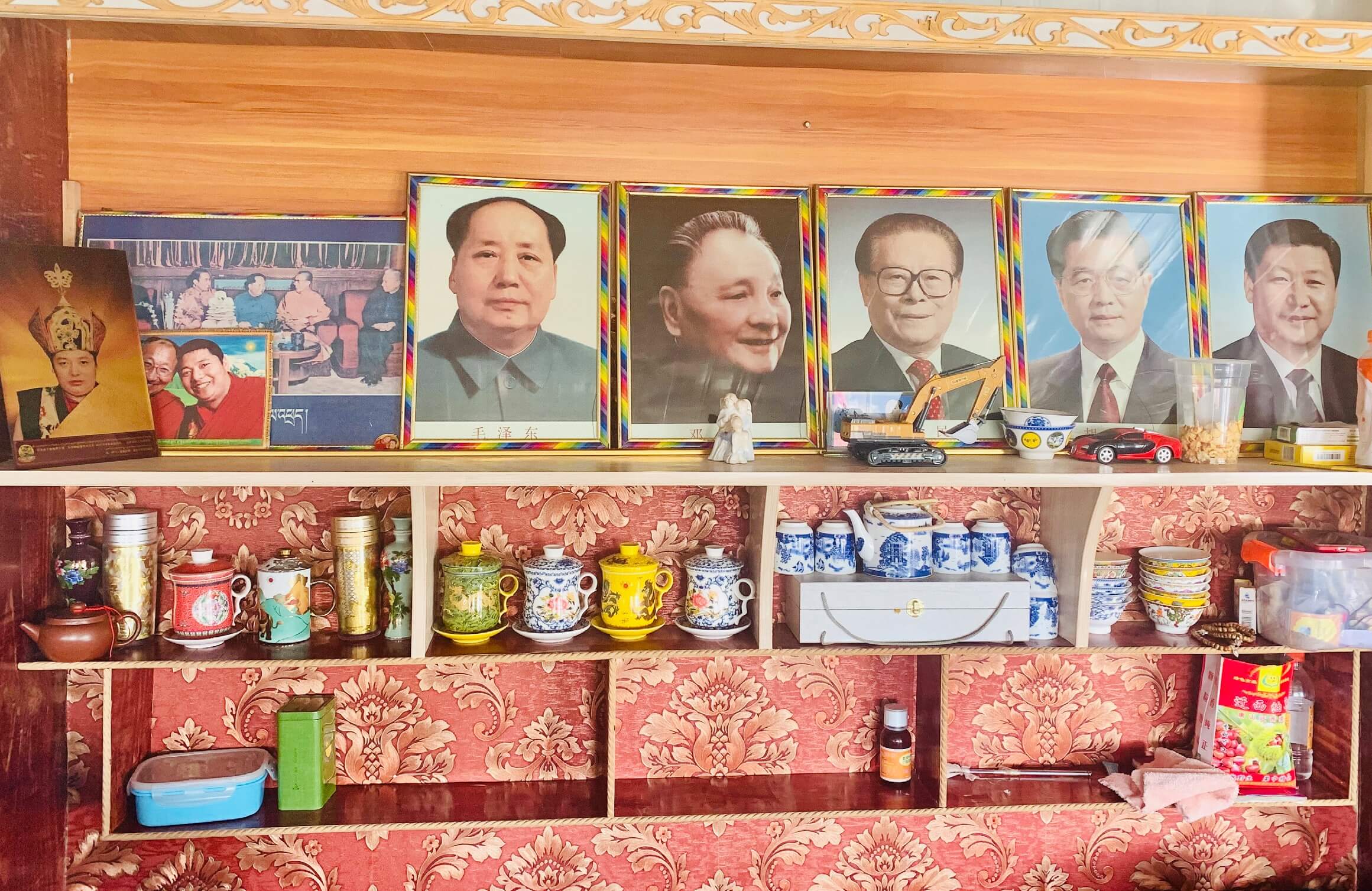

top: The portrait of the five PRC leaders (from left to the right: Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping) is often seen in the winter houses and resettlement centres in rural pastoralist China. According to local pastoralists, this is one of the requirements from the government. For the local government, this is the way to show pastoralists’ gratitude.

bottom: A 2020 protest in Cagliari in front

of a regional government building. Pastoralists

demand a regulatory framework for the milk

chain and a fair price for the milk they produce.

technologies

New and old forms of technology are juxtaposed in the pastoral landscape. Continuous innovation is essential in order to live under highly variable conditions. Often the most simple, durable, portable and repairable technologies are used as ways of responding to diverse uncertainties.

top: The jessours represent a persistent technology essential for the pastoral economy. These stone walls, previously built and maintained by hand, act as water and sediment catchment systems. As they are distributed in the valleys of the mountainous region of southern Tunisia, they ensure that part of the runoff and fine sediments are retained, while the rest passes to other jessours located downstream. By spatially and temporally distributing water, this system not only allows the cultivation of olives and dates, but also provides good pasture for livestock throughout the mountainous region, extending the grazing season.

bottom: ‘Please contact me if you want to buy (rent) pasture.’ With the wide use of mobile phones and the spread of social media platforms such as WeChat in rural regions, pastoralists find it easier and faster to promote rangeland leasing and renting on social media in Golok, Amdo Tibet.

from top left, clockwise: Rabari pastoralist selfies; Solar panels in a pasture in Golok, Amdo Tibet; A traditional birdhouse and windmills in Kachchh; Spraying goats with medicine in northern Kenya; Automated milking in Sardinia; A solar panel on the roof of a traditional pastoralist home in Ethiopia.

mobilising identities

Tradition is not timeless or fixed. Forms of identity create continuity despite uncertainty and change. Whether through institutions, material culture or ways of dress, customs rooted in the past are carried into the present.

top to bottom: Pastoralists in the Sardinian plains pose for a photograph demonstrating their work during birthing season by helping a newborn lamb to feed. Their dress is a combination of old traditions (the velvet trousers) and new (camouflage jackets).

A school organised outdoors for pastoralist students in the Banni grassland region of Kachchh district.

The son of a spiritual leader in Borana should not cut his hair as it symbolises the spirituality that transfers from father to son. Now a student in primary school, he fears his non-Borana teachers will make him cut it.

A school organised outdoors for pastoralist students in the Banni grassland region of Kachchh district.

The son of a spiritual leader in Borana should not cut his hair as it symbolises the spirituality that transfers from father to son. Now a student in primary school, he fears his non-Borana teachers will make him cut it.

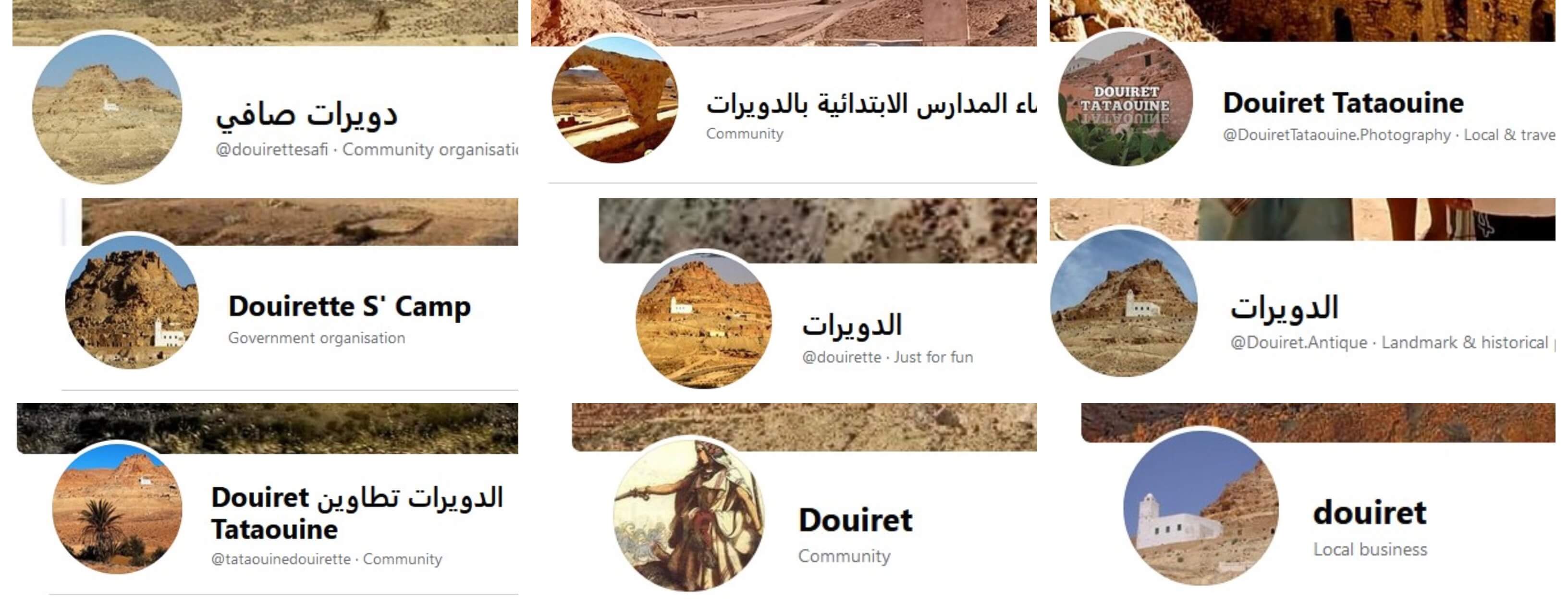

Social media is an important hub for Douiret’s extended community to engage with each other. Through Facebook, for example, the diaspora continues to exchange likes, images, poetry, portraits, obituaries and comments with those that have remained in Douiret and vice versa. Through twenty active groups or pages dedicated to Douiret, various personalities from far and near exchange detailed information around the politics, history and culture of Douiret, cutting across social background, class and gender. As identities are mobilised online to participate in conversations across Douiret, the boundaries between absence and presence are yet again challenged.

above: In Gomole, Borana, the practice of exchanging pasturelands, permanently or temporarily, for farmlands can be seen in homes. Attire and utensils once linked to livestock rearing must be moved to accommodate the new entrants.

right: The practice of Tibetan Buddhist rituals is often one of the strategies that local pastoralists use to respond to uncertainties. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kokonor pastoralists made thousands of statues and buried them underground for better luck in the coming year.

right: The practice of Tibetan Buddhist rituals is often one of the strategies that local pastoralists use to respond to uncertainties. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kokonor pastoralists made thousands of statues and buried them underground for better luck in the coming year.

markets

Pastoral economies are subject to diverse uncertainties. Variations in market price, regulations and consumer behaviour all shape the way pastoralists negotiate market arrangements and practices of selling.

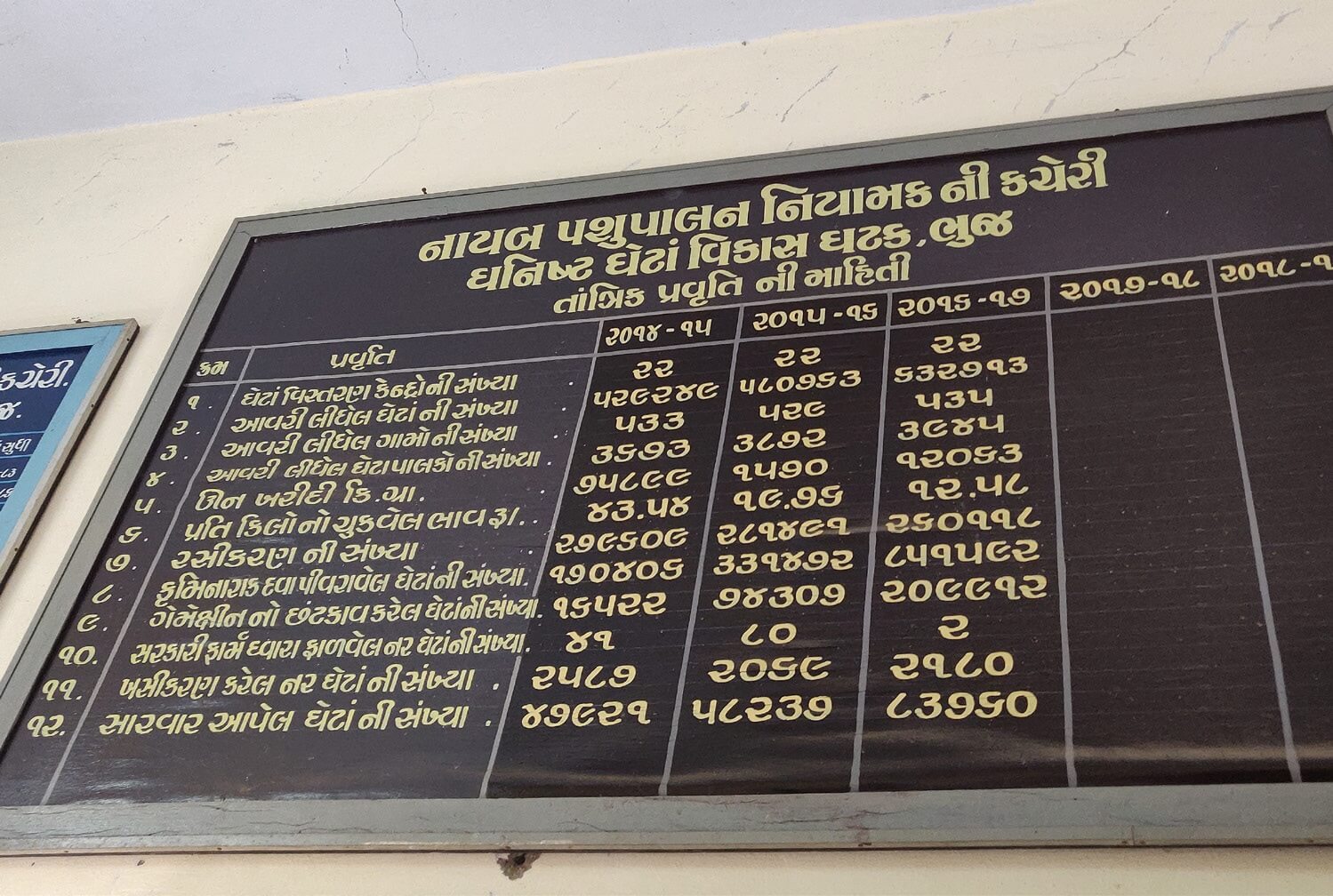

The Rabari were specialised producers of coarse wool. Now, with greater imports of fine wool and synthetic alternatives, the wool market for their produce has collapsed. The information board in the Gujarat Sheep and Wool Development Cooperation (GUSHEEL) office in Bhuj, Kachchh indicates this decline. The highest price that the pastoralists received for their wool was Rs. 20-25 per animal; now instead of receiving money, they must pay Rs. 5-7 per animal for shearing.

far left: Camel milk sellers on the roadside in Ethiopia.

left: A women-led camel milk cooperative in Isiolo supported by multiple NGOs.

below: Artisanal producers in Sardinia often sell directly to consumers in small shops or online.

In the past buyers and sellers would bargain over the price of small livestock, but now scales are used to weigh goats and sheep to determine the price based on market standards. Market uncertainty persists for camels and cattle, for which there is no set price per kilogramme.

A livestock trade market abandoned by pastoralists in a township centre (below). Traders now come directly to summer and winter pastures with trucks to pick up livestock. Since the end of collectively managed markets for livestock and pastoralist produce, small businesses have revived. Both locals and non-locals are constantly involved in different types of business in different seasons. Chinese businesspeople from the eastern part of Qinghai are most active during the early summer season. They bring cheap urban merchandise such as clothes and other necessities to the pastoralists (bottom image).

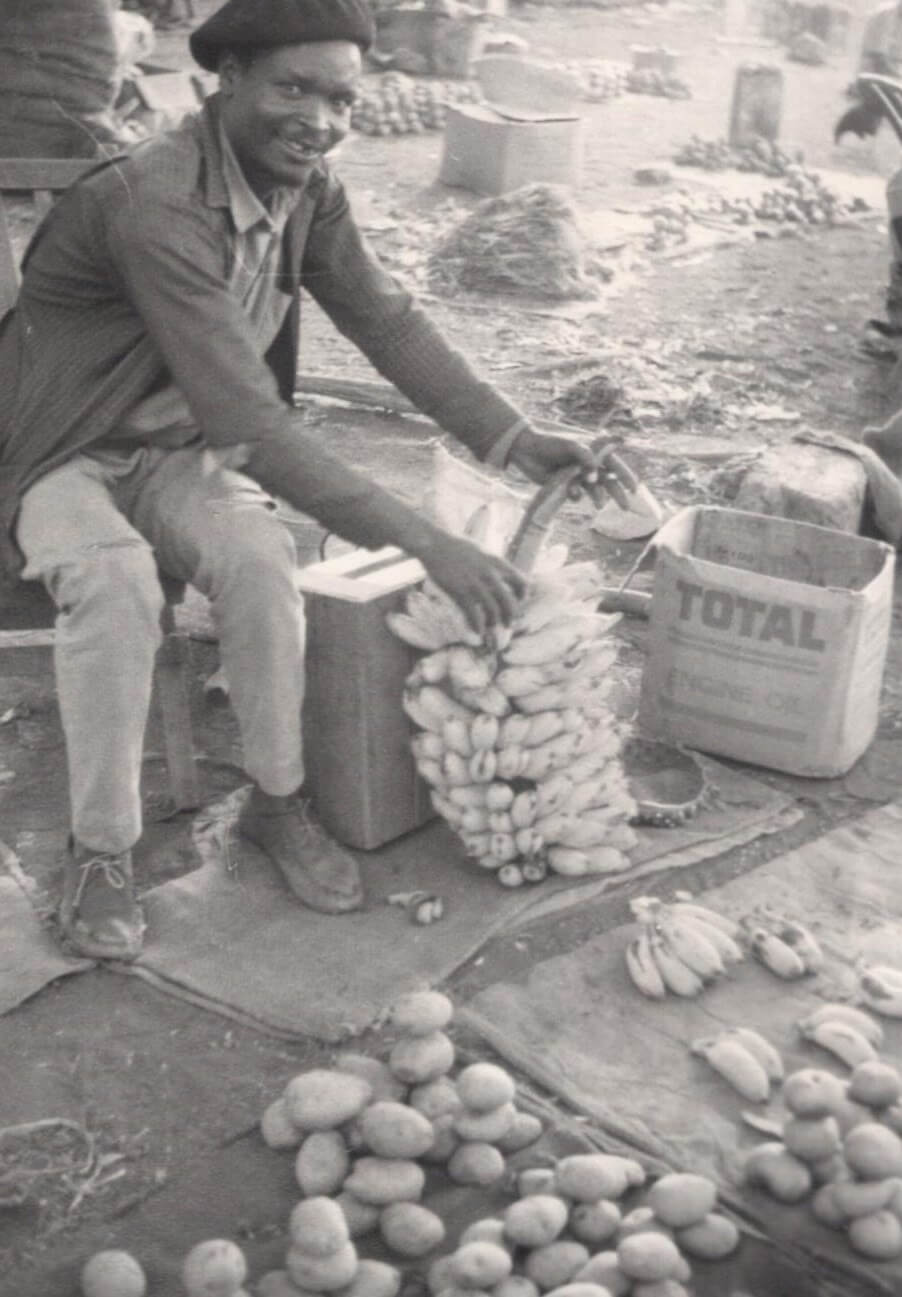

from left to right: The market in Dubluq, Ethiopia in 2020; The market in Isiolo, Kenya in the early seventies.

credits

Photography: Natasha Maru, Nipun Prabhakar, Palden Tsering, Giulia Simula,

Linda Pappagallo, Hamdi Dallali, Tahira Shariff, Masresha Taye, Michele Nori,

Vibhabhai Rabari, Gudrun Dahl, Goracha, Doyo Loko

Additional photography: PASTRES photovoice participants

Photovoice Advisor: Shibaji Bose

Photo Editing and Newspaper Design: Roopa Gogineni