douiRet, tataouine

tunisia

linda pappagallo

︎︎︎ download newspaper (english)

︎︎︎ download newspaper (french)

︎︎︎ download newspaper (arabic)

Linda has worked on pastoralism in the Middle East and North Africa. Her research with the PASTRES project explores the role of migration, and various forms of absence-presence, on livestock keeping in southern Tunisia.

At the end of a windy road,

at the very edge of the Dahar mountainous range, and in between the dry rocky canyons,

at the very edge of the Dahar mountainous range, and in between the dry rocky canyons,

Douiret is a village that you arrive to and not pass through.

Elders, children and women seem to dominate the demographic scene

when walking through town,

when olive picking,

or when taking the transportation to Tataouine

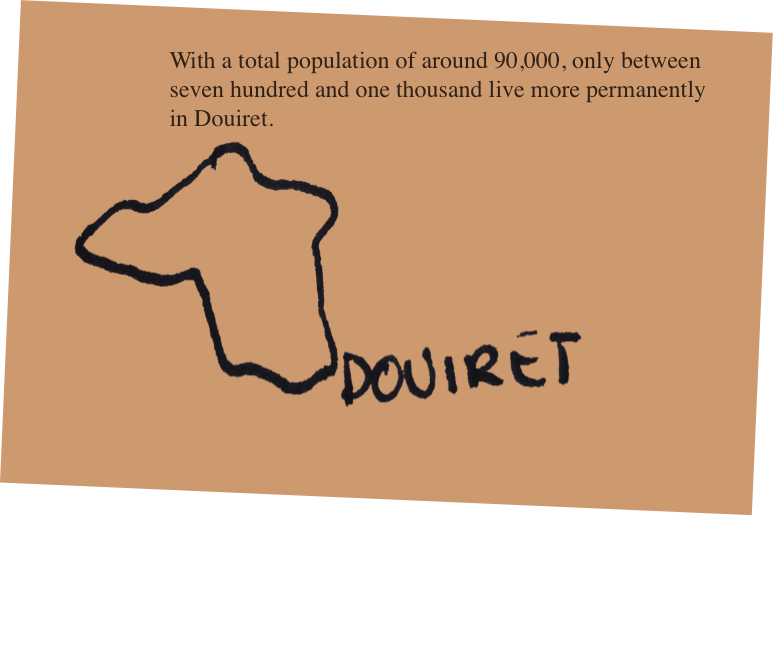

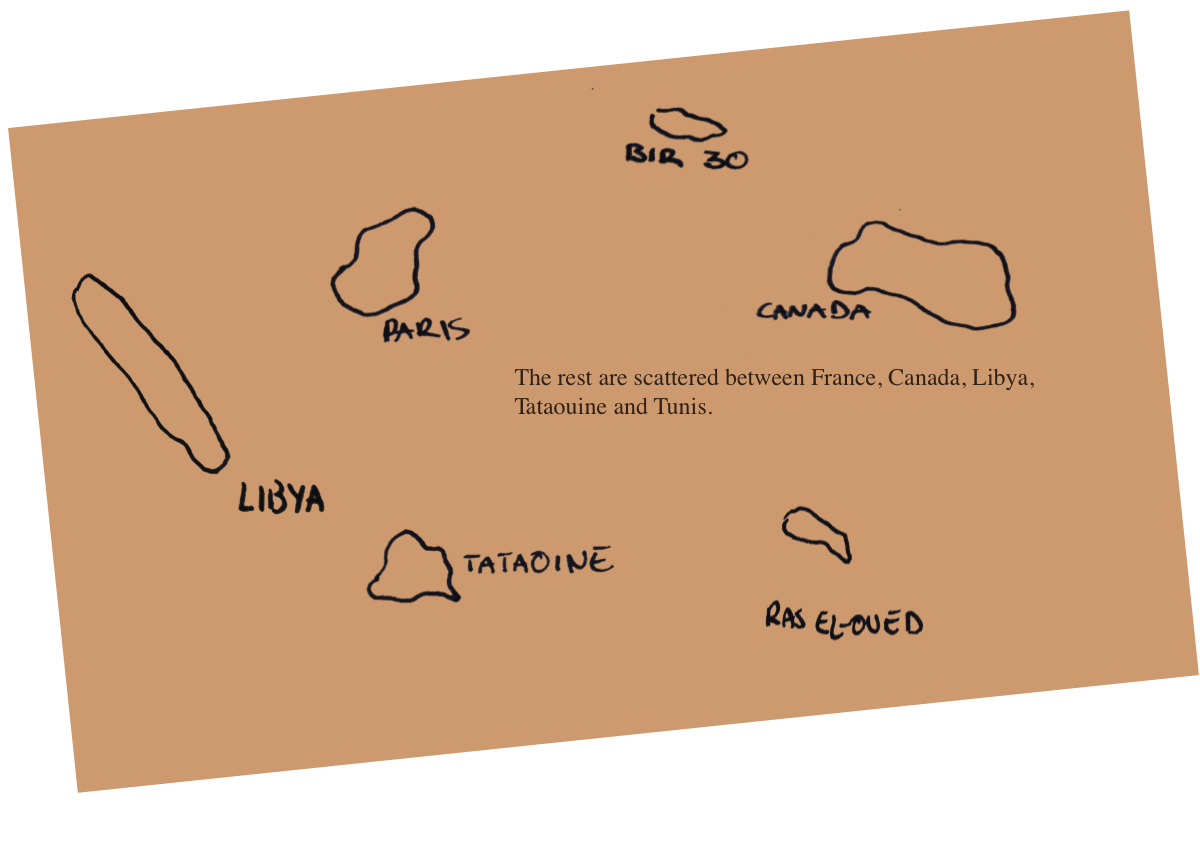

This however is a demographic mirage.

If one stays long enough, in this Amazigh mountain village in Southern Tunisia,

one can notice the expansion and contraction of Douiret’s population;

marked by seasonal returns,

of school holidays, sheep shearing, olive picking, weddings in the summer months and festivities

such as Eid Ekbir or Ramadan.

Who is present and who is absent?

Who leaves and who stays?

Who returns and who does not?

Who leaves and who stays?

Who returns and who does not?

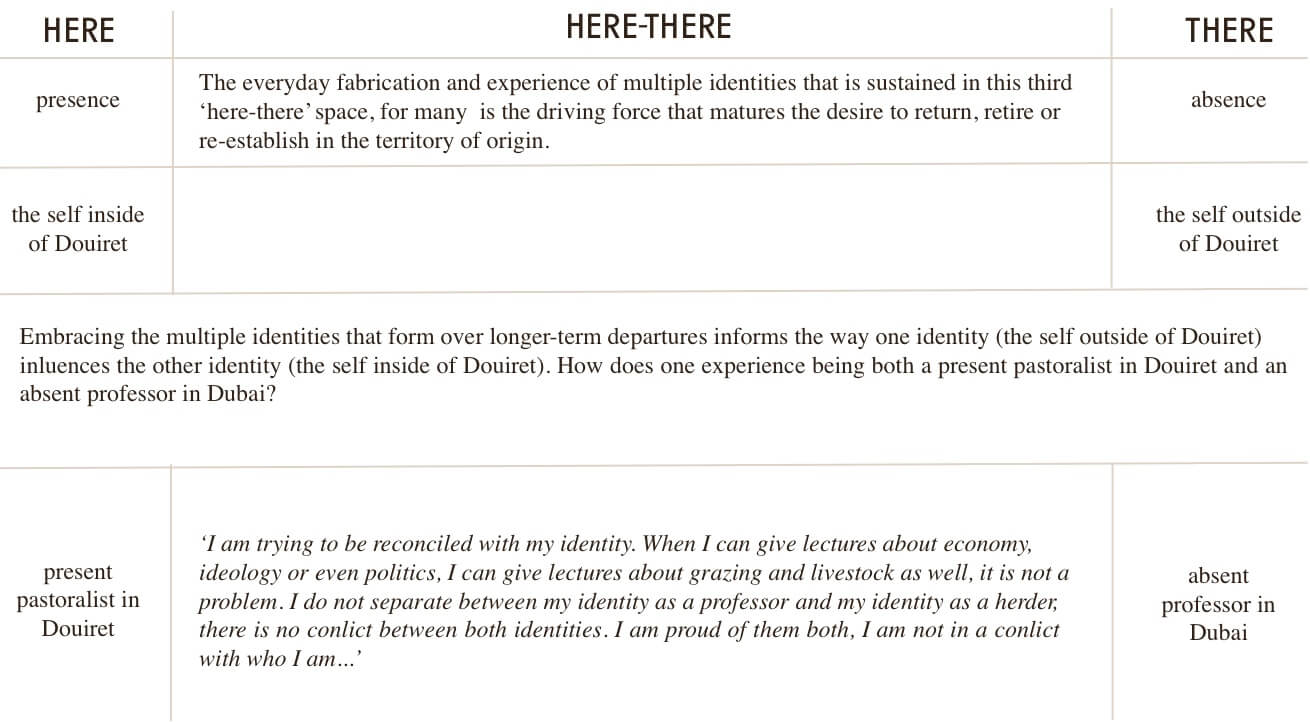

“Partir pour rester”, to leave in order to stay, illustrates the connection between two seemingly opposite actions, leaving and staying. The act of ‘leaving’, as a form of absence, is in relation to ‘staying’ as a form of presence. Absence is just another form of presence. One may leave in order to stay or leave in order for others to stay, or leave in order to stay later. Absence can therefore be seen as the necessary ‘Other’ to presence. Absence is enacted along with presence; it is constituted with it, and helps to constitute it.

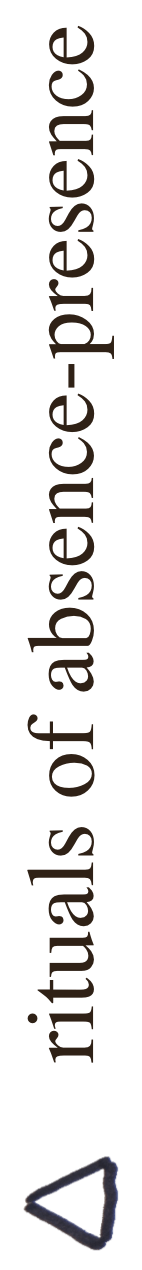

The changing enactments of presence such as the frequent returns during festivities, sheep shearing or olive picking are combined with virtual presences on Messenger and WhatsApp, redefining what absence means today. These changing forms of absence-presence through rituals, liminalities, asynchronicities and vacuums influence the relationships between people and livestock.

The changing enactments of presence such as the frequent returns during festivities, sheep shearing or olive picking are combined with virtual presences on Messenger and WhatsApp, redefining what absence means today. These changing forms of absence-presence through rituals, liminalities, asynchronicities and vacuums influence the relationships between people and livestock.

‘Leaving could mean emigration, like those who left for France and never came back, they left once and for all, they no longer remember Douiret. Then there are those who came back and yet they don’t want to remember or recognize Douiret as their home. They would leave and in the course of two or three generations the children, who were born abroad, no longer know Douiret and even if they visit, they come as tourists or they might visit to study history. The ones who no longer remember Douiret have intended to never come back since

they left. However, there are those who have emigrated to find a living elsewhere but their families remain here, so they come home once a year during their vacation. They might leave their wives and kids here and they would spend their one-month vacation with them and spend the remaining 11 months working abroad. They would live this way until they retire and that might take 10 to 15, 20 years or more depending on how young they were when they left.’

The ritual of bringing sons and daughters regularly “to the village”, and the rhythmic returns marked by the agricultural and the school calendar build imaginaries and identities through childhood memories.

The memories of herding during school holidays, or coming back to the village for olive picking or of sheep shearing, ensure relationships to territory are built over time.

‘For instance when I used to be in university and come home for Eid for three days, I would herd. When I was in the Louage on my way back home, my father would call to ask where I was and if I would say that I reached Tataouine, he would then tell me to bring my Balgha along . You know that balgha is the shoe that herders wear.’

The memories of herding during school holidays, or coming back to the village for olive picking or of sheep shearing, ensure relationships to territory are built over time.

‘For instance when I used to be in university and come home for Eid for three days, I would herd. When I was in the Louage on my way back home, my father would call to ask where I was and if I would say that I reached Tataouine, he would then tell me to bring my Balgha along . You know that balgha is the shoe that herders wear.’

But identities in relation to territory are not only built by returning to the village, but also through the coming and going of visitors from Douiret.

‘This coming and going creates a sort of continuity for me, for my mother and my younger sister. This continuity manifests itself every time someone comes, when we receive letters, when someone says that it has rained in Douiret. So this relationship with the village is virtual, not real, and manifests itself with people that come, with couriers, with good and bad news. We continue to live the village in an imaginary fashion, in a virtual fashion, we continue to keep the images of our childhood vivid. The caves, school, the olives, the dromedaries.’

‘This coming and going creates a sort of continuity for me, for my mother and my younger sister. This continuity manifests itself every time someone comes, when we receive letters, when someone says that it has rained in Douiret. So this relationship with the village is virtual, not real, and manifests itself with people that come, with couriers, with good and bad news. We continue to live the village in an imaginary fashion, in a virtual fashion, we continue to keep the images of our childhood vivid. The caves, school, the olives, the dromedaries.’

“el ghayeb houjjetou maâh”

“Those who are absent are always wrong.”

This proverb speaks about the loss of power of negotiation for those who are not visible, or not somehow enduringly present.

The question around time is pertinent. How long someone is absent for is connected to the quality, or form of presence. Presence not only requires time, but it requires a particular kind of time, a tempo, that the place of origin demands and is accustomed to.

‘The most important thing around absence is losing the power of negotiation. Presence requires time. There is a problem of time. There is a problem of time in terms of duration and time in the sense that everyone has their time, their tempo. Tempo is the rhythm of time. You have time in the general sense but the tempo is not the same for everyone. Everyone has their own tempo. The one in the terrain has their notion of time, difficult to identify. The tempo holds the clock of the time. The one who is not there has a limited time… the one who is there has all the time of the region. And the one who arrives has left his time in Tunis, in Paris. It is almost burlesque, comical.’

This burlesque sensation illustrates what happens when an absence that is synchronous to local social, political, cultural, and economic dimensions, becomes asynchronous, perhaps eclipsing into ruptures.

The unspoken side of returning is one that exposes the vulnerability of attachment to place. Leaving and staying, or maintaining a sort of ‘synchronicity’ with place of origin, is therefore not simple; it is a fine balance, a tempo, that requires considerable emotional and material investment in social relations and territory.

We are in an epoch where the visual is very important. The photo, the symbol, the tatouage, the weaving. There are differing reactions to these that are subject to the accumulated baggage of each individual, because in some ways it is a relation between a symbol, a colour and carpet and then a return to the personal imagery which for some is the troglodyte of their grandparents, for others the palm and the symbol of the palm tree. Those who are in Paris/Canada will react differently from someone who is in Tataouine.’

The visual and virtual are tools that influence the immaterial aspects of attachment to a place of origin. With over 20 active Facebook groups or pages dedicated to Douiret, and thousands of individual pages of Douiris across the globe that are actively posting on all matters that relate to Douiret and the region, physical absence is complemented by a virtual presence. This is through historical colonial texts, archival footage and pictures, manuscripts, land titles, maps, obituaries, poetry, legal claims and cases, governmental decisions and real-time meetings, as well as live Facebook videos of sheep shearing, olive picking, and carpet weaving.

The visual and virtual are tools that influence the immaterial aspects of attachment to a place of origin. With over 20 active Facebook groups or pages dedicated to Douiret, and thousands of individual pages of Douiris across the globe that are actively posting on all matters that relate to Douiret and the region, physical absence is complemented by a virtual presence. This is through historical colonial texts, archival footage and pictures, manuscripts, land titles, maps, obituaries, poetry, legal claims and cases, governmental decisions and real-time meetings, as well as live Facebook videos of sheep shearing, olive picking, and carpet weaving.

A Douiri woman plays with her goats. They only have a symbolic number to keep them company in their old age.

Absences create vacuums of opportunity. As men leave, and wives and children remain back home, women may take on more masculine aptitudes, roles, responsibilities and objectives. As women’s roles shift, in the household and in the community, absences have gendered dimensions. Behind a man that “leaves in order to stay”, there are (several) women that stay in order for the men to leave. “Elles restent pour qu’ils partent” – they (feminine) stay so that they (masculine) can leave. This is the other side of leaving, where wives, daughters, sisters, mothers and female relatives stay in Douiret to support the family and to allow for accumulation of possibilities elsewhere.

‘If it wasn’t for women, we wouldn’t be able to do anything, women are everything. When I was in Tunis I had a lot of livestock here and I relied on my wife. She ran the business, she bought hay for the sheep and herded the flock and spent from her own money to keep things going. If I were to do it alone I couldn’t have achieved that. My daughters helped her as well, without the help of my daughters and my wife I couldn’t have raised livestock.’

‘If it wasn’t for women, we wouldn’t be able to do anything, women are everything. When I was in Tunis I had a lot of livestock here and I relied on my wife. She ran the business, she bought hay for the sheep and herded the flock and spent from her own money to keep things going. If I were to do it alone I couldn’t have achieved that. My daughters helped her as well, without the help of my daughters and my wife I couldn’t have raised livestock.’

above: The daughter of an important livestock owner in Douiret directs the male dromedary first, followed by the female and lactating dromedaries, towards feed composites she has prepared with the help of her brothers. Although they own a large herd of sheep, the increasing frequency of droughts has pushed this family to increase investments in dromedaries as they fare better and are more profitable in such conditions.

below: The sister of a herder and livestock owner has worked for over twenty years, day in and day out, in maintaining the family flock. In the mornings she works as a cleaner in a small hotel, at noon she tends the goats in preparation for her brother to take them out to pasture, and in the afternoon, she herds their flock of sheep.

below: The sister of a herder and livestock owner has worked for over twenty years, day in and day out, in maintaining the family flock. In the mornings she works as a cleaner in a small hotel, at noon she tends the goats in preparation for her brother to take them out to pasture, and in the afternoon, she herds their flock of sheep.

credits:

Photography: Hamdi Dallali (@hamdi_dallali) and Linda Pappagallo

Illustrations: Linda Pappagallo

Photovoice Advisor: Shibaji Bose

Photo Editing and Newspaper Design: Roopa Gogineni

pHotovoice

Beyond seeing pastoralism as a livelihood, as a way of life, that responds to various uncertainties, livestock provides a stable job and a viable alternative to living in the city. Unemployment in the south of Tunisia reaches 30% and is a major concern for the younger generation, causing significant emotional and physiological distress.

These photovoice stories portray the lives of two young entrepreneurial livestock owners, Mohammed and Said, both aged between 30-35 from Douiret in the region of Tataouine. By using disposable cameras, their stories are illustrative of the everyday life of nascent livestock owners who have returned to their place of origin to escape emotional and physical precarity, and whose flocks provide mobility, health, employment and business.

These photovoice stories portray the lives of two young entrepreneurial livestock owners, Mohammed and Said, both aged between 30-35 from Douiret in the region of Tataouine. By using disposable cameras, their stories are illustrative of the everyday life of nascent livestock owners who have returned to their place of origin to escape emotional and physical precarity, and whose flocks provide mobility, health, employment and business.