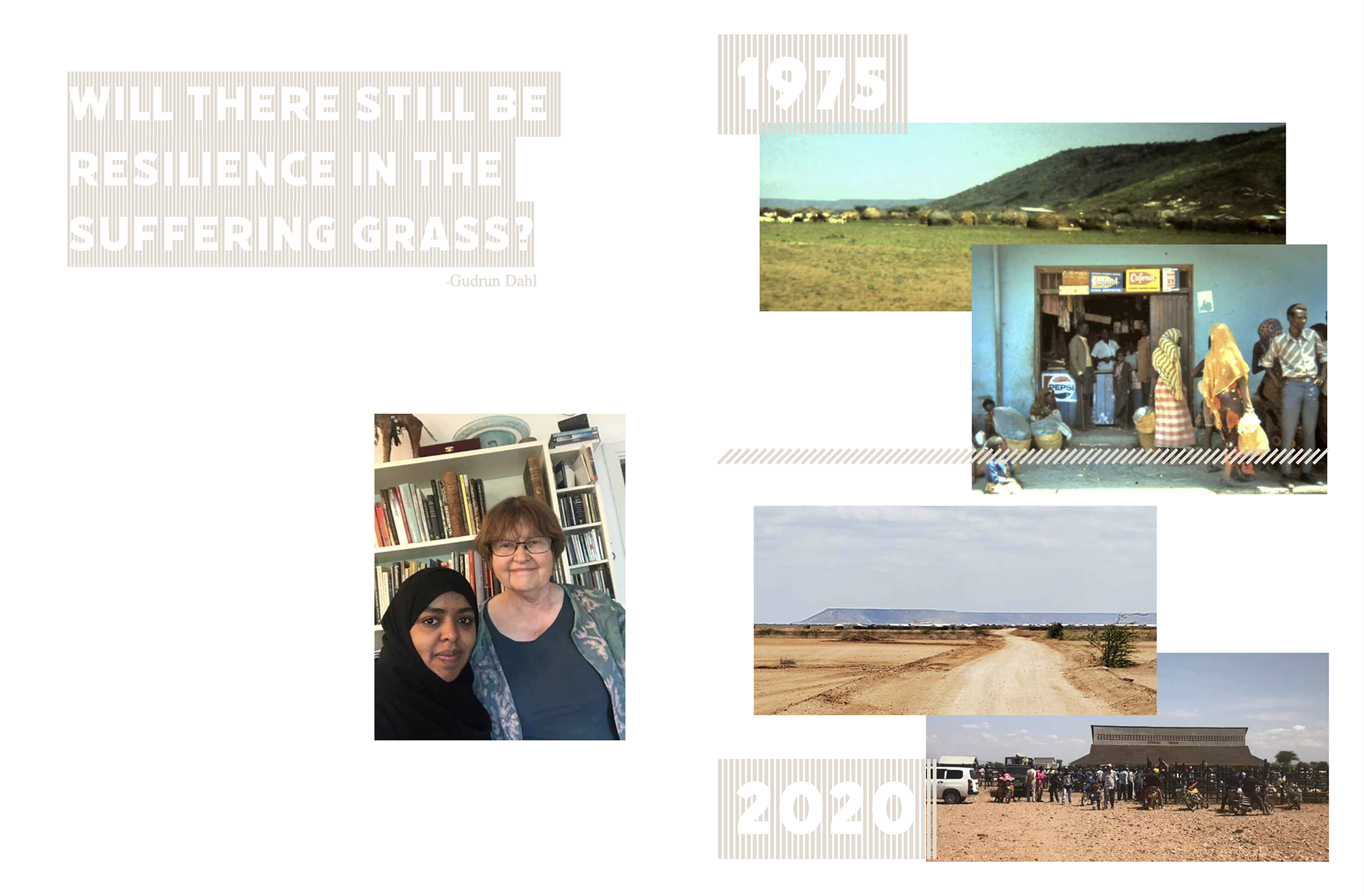

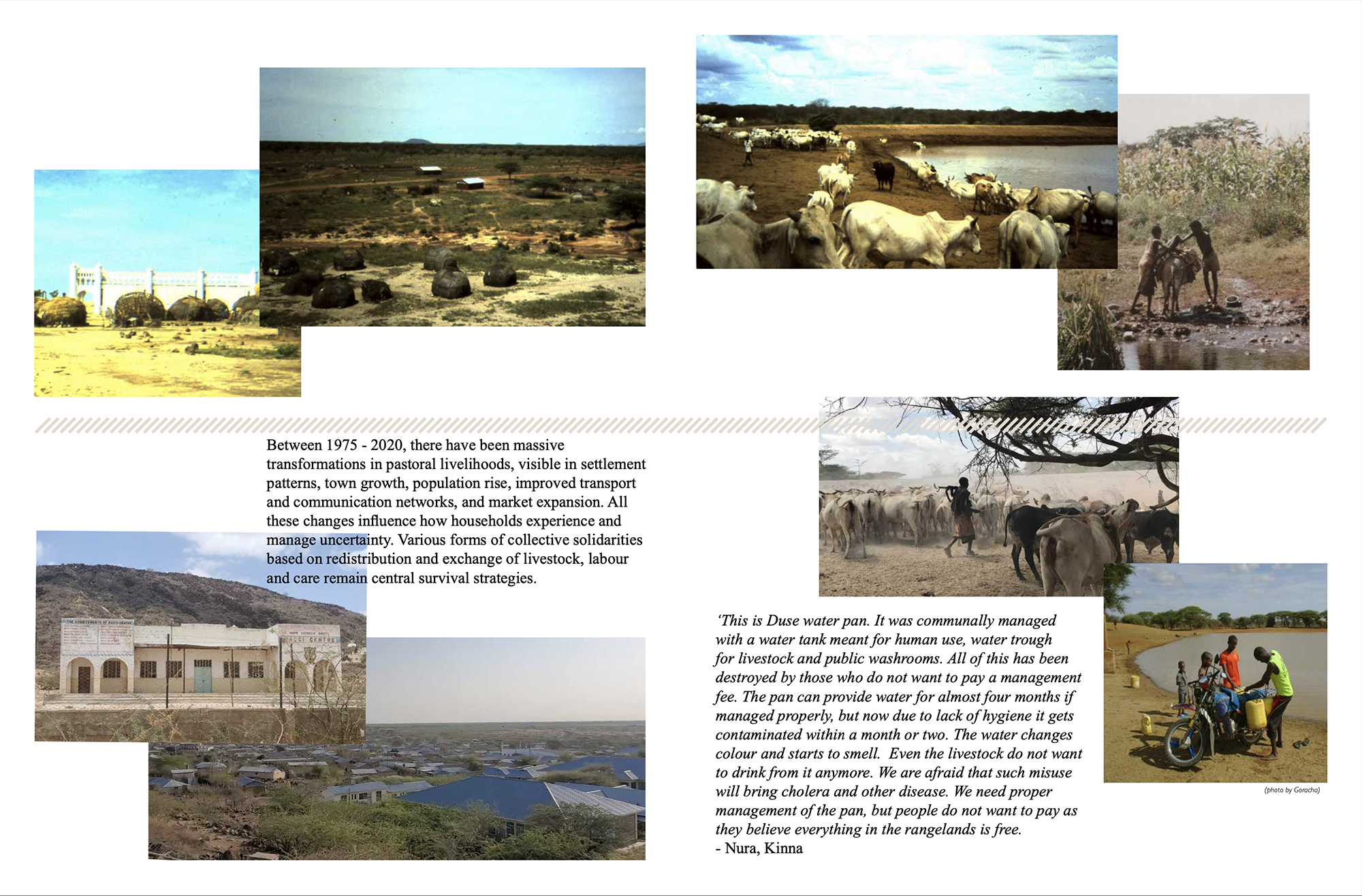

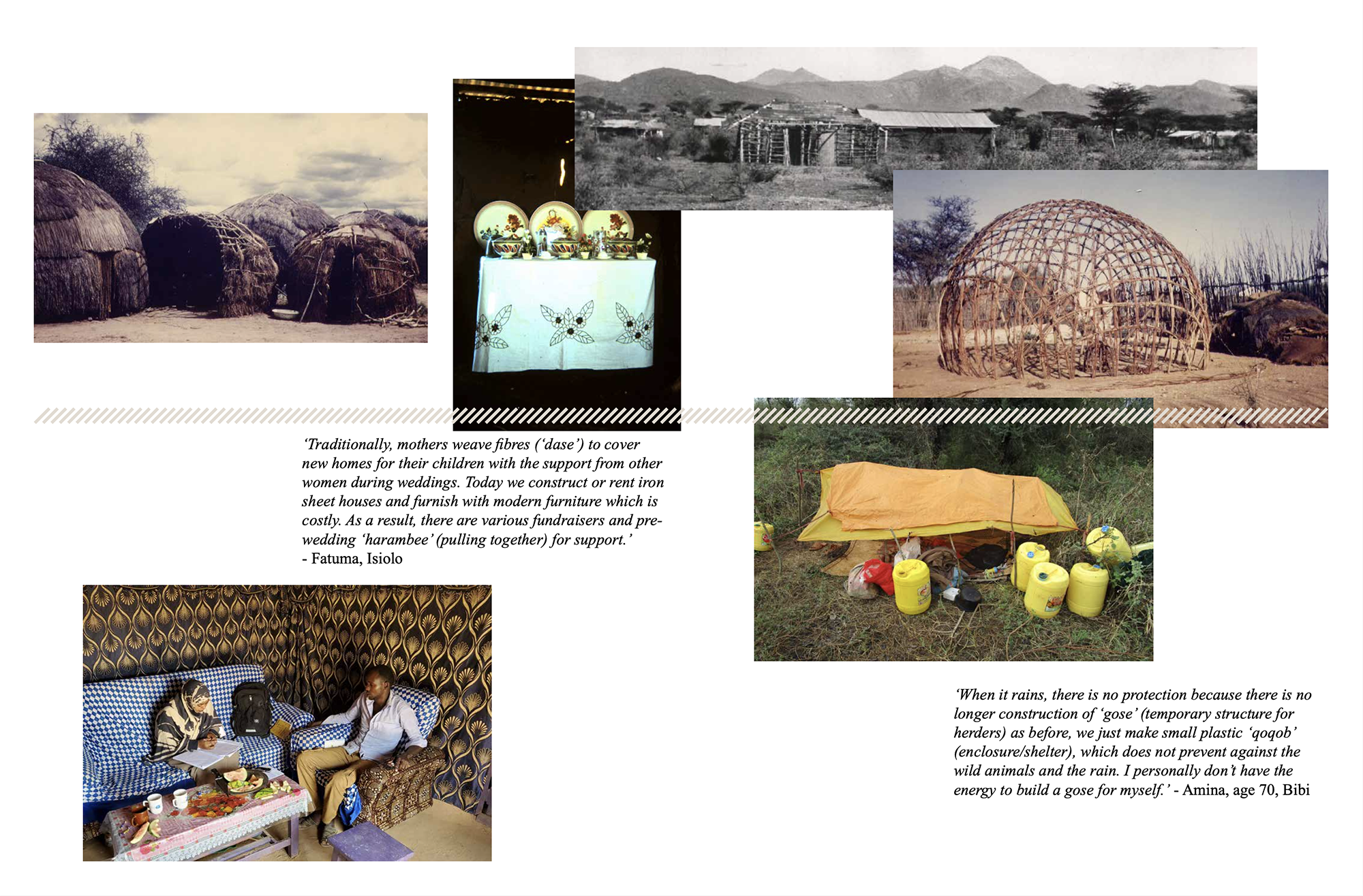

Tahira’s research looks at changes over time in forms of uncertainty and moral economy practices among the Waso Borana pastoralists of Northern Kenya. In 1975, Anthropologist Gudrun Dahl began studying the Borana pastoralists’ social-economic context through ethnographic research. Looking at the changes and the continuity of livelihood practices through the lens of uncertainty and moral economy between 1975 and 2020 provides a broader understanding of society’s structural transformation, a key component of development research.

photovoice

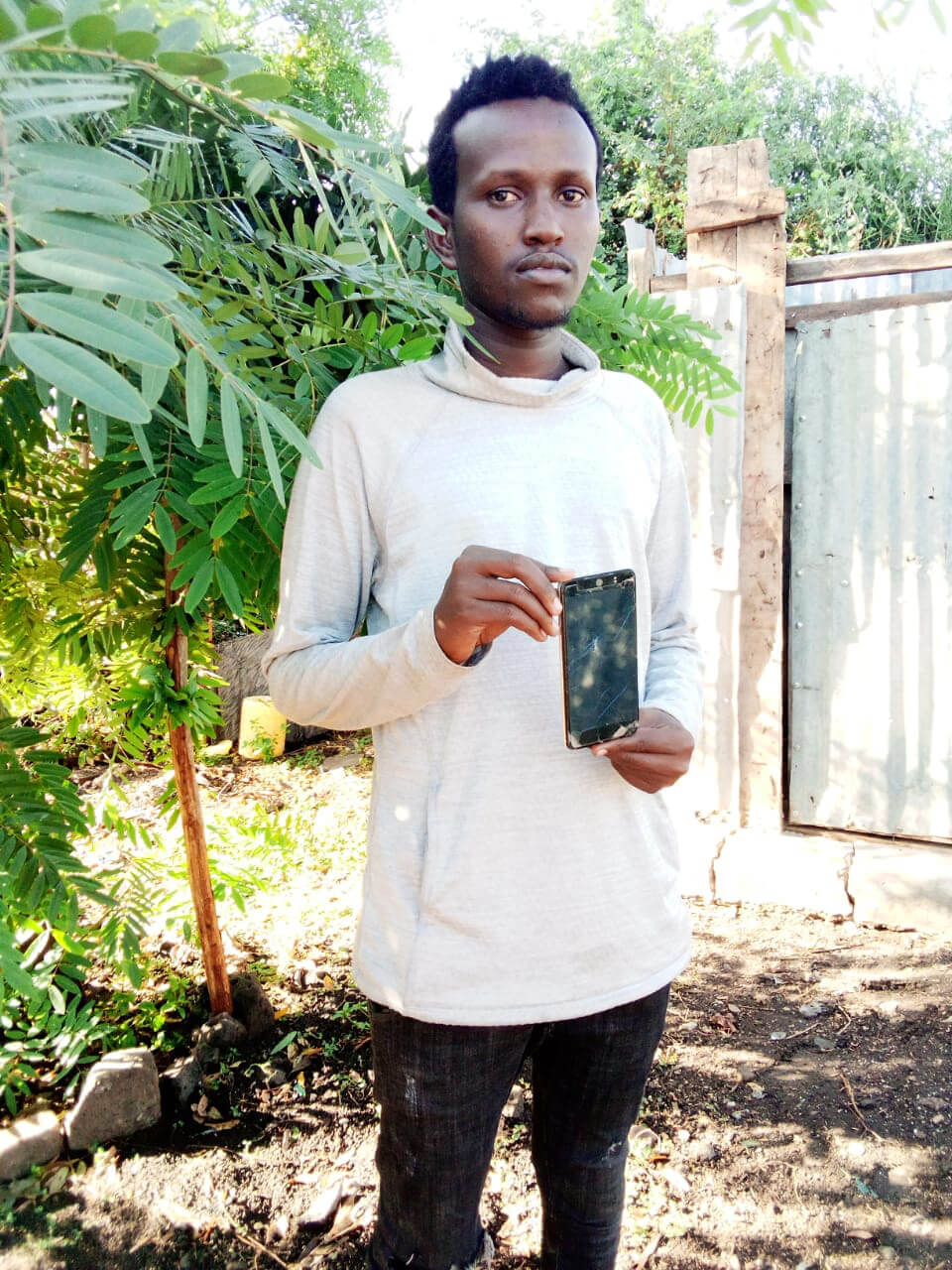

This research used photovoice to generate knowledge about uncertainty, moral economy and changes over time. The process was carried out with several groups, including older pastoralists, young males, and girls and boys from Kinna and Merti. The participants shared their photos and narratives through WhatsApp due to the Covid-19 related lockdown. Each session lasted two weeks and ended with a group discussion. Participants reported on the challenges of the process, such as broken phones.

‘The Acacia is not just another tree in the drylands, it holds a special place in our hearts. Many pastoral towns are named after Acacia trees. Birds use them as shelter for their nests, we also use them for keeping beehives. On dry sunny days, they provide good shelter to the livestock and the herders. We are losing this prime tree to the charcoal burners. We need to educate people on its importance. Charcoal benefits an individual once, but the Acacia serves the entire dryland population.’

- Ralia, Kinna

turning variability

into opportunity

‘ We currently have a new labour force: we call them “corona herders”. Some parents have sent young boys and girls to live outside to assume the traditional role that were lost to modern education. This has relieved the strains on family labour requirements and many parents are happy.’

-Dabbo, Merti

‘I am Ralia and I am in High School. Covid-19 led to school closure and I have been home for many months. Many children have been a burden on their parents because they require meals and remain idle. I wanted to be productive for myself and for my mother. I requested to use our neighbour’s vacant plot and planted onions. I invited a few women to help in planting and weeding. Now my onions are ready, and the earnings can help in my school fees. It’s about how you manage the problem, you can twist and benefit from the other side of the coin rather than focusing on the bitter side.’

- Ralia, Kinna

borani waali waheela

amalee walii waarega.

borana are companions

to each other and feed each other.

‘The cow fell into a well. Nobody could go inside the well because the cow was frustrated, but we wanted to save it by any means. Here comes the natural instincts of being your brother’s keeper. As pastoralists, we are afraid of enemies, drought and other uncertainties. Companionship matters to get access to protection and security in times of crisis.’

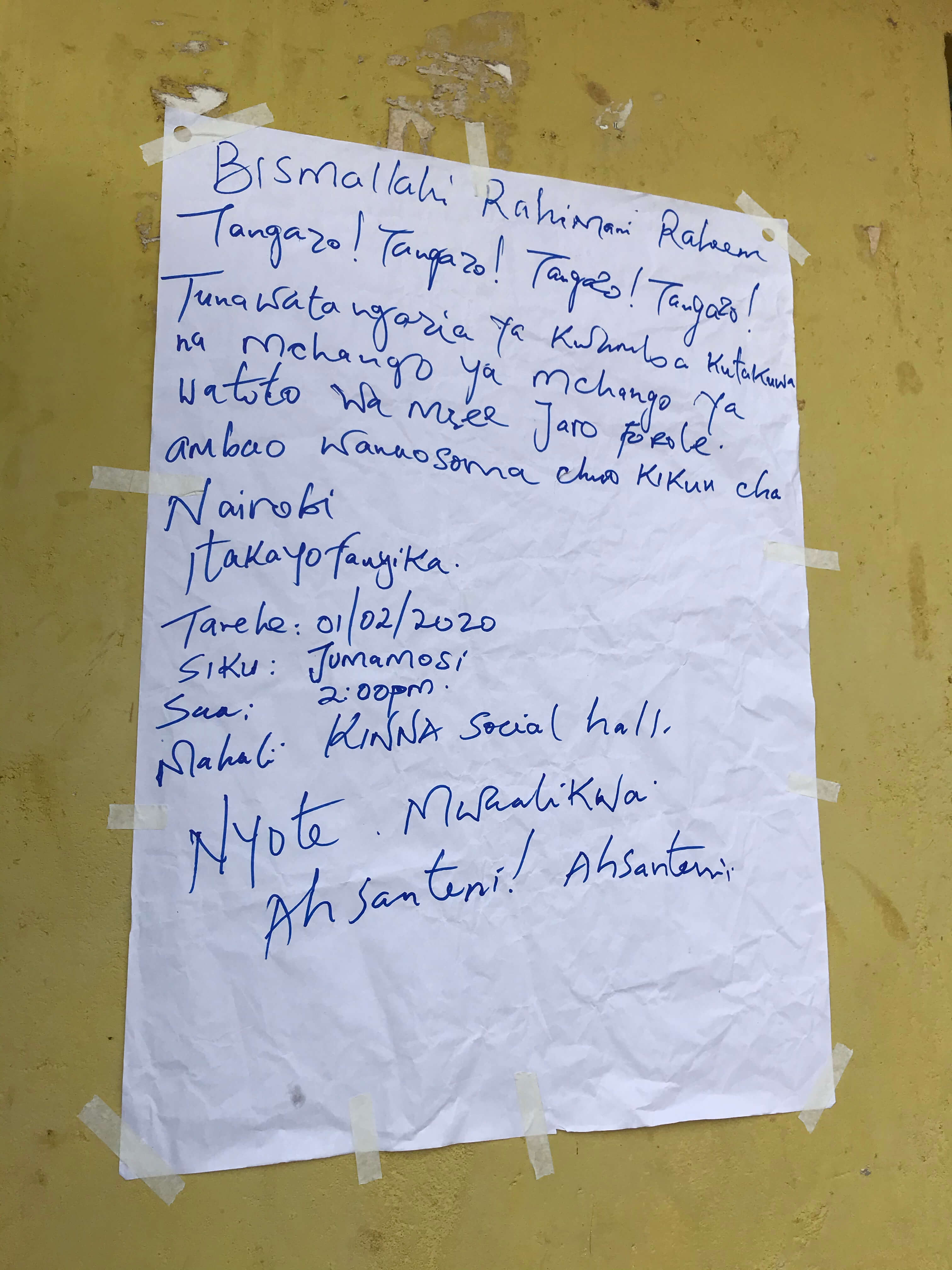

‘Advertisement! Advertisement! We inform you that there will be a fundraiser for the children of Mzee Jaro Farole who are studying at the University of Nairobi. You are all welcome. Thank you!’

Kinna residents gather to condemn extrajudicial killings by Kenya Wildlife Service rangers in May 2020. Collective response to crisis is a vital strategy for pastoralists in town to manage variable conditions such as conflict and insecurity.

credits:

Photographs above red line: Gudrun Dahl

Cover photo: Goracha

All other photography courtesy of Tahira Shariff

Photovoice Advisor: Shibaji Bose

Photo Editing and Newspaper Design: Roopa Gogineni

pHotovoice

The uncertainty of rangeland

resources exploitation: ‘The curse of Yamicha and Prosopis encroachment’

Yamicha!

‘The calling’ what future for the ‘calling’?

Yamicha!

‘The calling’ what future for the ‘calling’?